Table of Contents

Companions in games

Part of Project Lirec

A very important aspect of HRI is looking at how people react to artificial companions. Games give us a wealth of easily accessible information on people's attitudes and experiences of playing and problem solving alongside non-player characters (NPCs). Although the complexity of technology involved varies, it's not always the more advanced solutions which work the best, as a consistent and carefully constructed game environment can work with the constraints of the technical limitations and still produce an experience which people enjoy, and spend hours exploring.

From a good article on NPCs and immersionIf an enemy monster is stupid (because its “brain” is just a couple of hundred lines of computer code running on a personal computer that is busy doing a lot of other stuff) it isn’t too bad. Hey, it’s a monster. It’s not supposed to be smart. But when a human character shows up the player expects him or her to act like a human. Then when they walk into the player’s line of fire, get confused by doorways, get caught up on scenery, or utter the same phrase for the tenth time, they are exposed as a fraud and the illusion of the gameworld is broken. NPCs have so many ways they can break immersion that it’s difficult to enumerate them all.

Rescue or gameplay helper companions

Some NPCs in games are designed to help the player in some form. This is a list of interesting characters who are either designed to provide some assistance in solving problems or fighting battles, or are a central theme of the game and therefore are intended to form a bond with the player.

| Companion | Gameplay purpose | Intelligence | Attachment level |

|---|---|---|---|

Yorda in Ico Yorda in Ico | To be rescued | General wandering, object avoidance, local route finding - lack of any direction or purpose until a cutscene script takes over. Talks in strange unintelligible language. | Quite high to begin with, followed by a trough when you realise she's actually quite annoying - e.g. inability to avoid being dragged away by the “shadows” that come after her. In the end you strangly feel attachment again, when she's taken from you - a sort of attachment due to persistence, an annoying friend that won't go away. |

Alyx Vance in Half-Life 2 Alyx Vance in Half-Life 2 | Cooperative play | Object avoidance, combat, use of terrain and cover, blind fire etc. Helping with level progression tasks and capable of showing excitement, dismay and anger. | Reception seems good from players, although some complaints about dialogue spoiling the effect with repeated and nonsensical chatter |

Dogmeat from Fallout 3 Dogmeat from Fallout 3 | Cooperative play | Dogmeat warns the player of danger, can be sent to search for items and distract enemies in battle. | Not such a good response from gamers on Dogmeat - he is not strictly required to play the game and can get in the way in battle situations. Also seems a little contrived as he miraculously appears when you need help. |

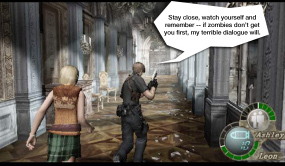

Ashley Graham from Resident Evil 4 Ashley Graham from Resident Evil 4 | Needs rescuing and helps with some gameplay | Following and object avoidance, pointing out possible solutions to puzzles | Not good on this character either, as being in the horror genre, it's very unforgiving to AI goofiness. The lack of attachment may also be due to the fact that unlike in Ico, where Yorda is with you all the time up to the last part, Ashley Graham often get recaptured. |

Floyd in Jet Force Gemini Floyd in Jet Force Gemini | Helps with gameplay/optional 2nd player control/sidekick | A pet/companion robot which has to be built by the player. Helps with battles, has infinite (low power) fire and is indestructible. | What is interesting about Floyd is that the fact that the player has made a contribution to his construction I felt the robot was more valuable to me as I had had to work at getting it and it wasn’t simply given to me (from Kassen). |

Pet companions

Unlike other games, pet games are solely concerned with creating an attachment with an artificial companion. In this way, the companion is the focus of the game. Other gameplay elements are introduced as a way of increasing the bond between the player and their pet. Most pet games are targeted at a younger audience, although in practice these games can have a much broader appeal.

| Game | Interaction | Attachment level |

|---|---|---|

Nintendogs Nintendogs | DS touchscreen for stroking and cleaning, and the microphone for training and talking to your puppy. | The NPC interaction feels very natural using the pen on the touch screen, and the voice control is done well - it takes a few attempts each time to learn commands, which fits well with the technical solution. The best selling game of all time, so it's doing something right. The portable nature of the DS console might largely be part of the success, along with the shameless use of dog breeds per game release. |

Tamagotchi Tamagotchi | 3 buttons, allowing you to feed, clean and play games with your pet. It tells you when it needs feeding, and dies if it's not attended to. | A huge success, which indicates a good attachment. So much so that it proved controversial due to children taking them into classes to keep them alive. Keeps well out of the uncanny valley as the Tamagotchi hardware (the name comes from the words egg and watch in Japanese) is very limited, so the display only tens of pixels across - which only adds to it's appeal. |

Chau Adventure, part of Sonic Adventure Chau Adventure, part of Sonic Adventure | Similar to Tamagotchi, but crucially, and of high relevance to Project Lirec the 'chau' pets migrate from the DreamCast console to a hand held device (either a VMU or a GameBoy Advance) and back again. The chau can be taken away and trained (or evolved) for various tasks in the main game, and can even be bred together by connecting two people's VMUs togther. | The chaus were not a core element of Sonic Adventure, so this feature was more of an experimental idea taking portable pets from Tamagotchi and integrating them with a full game. However, it was fairly successful and well received. |

Teams of companions

There are also examples of games which immerse the player in more complex social situations, involving groups working together, or squads fighting together.

| Game | Game description | Attachment level |

|---|---|---|

Pikmin Pikmin | The player has to grow and use small creatures called pikmin to retrieve parts of a ship which has crashed, and rebuild it to escape the planet. There are types of pikmin which have different abilities. Up to 100 pikmin can be active at one time. | The focus of the game is to interact with your pikmin as they help you to solve problems and carry out tasks. The game works well due to the large quantity of individuals, which is a much more forgiving strategy than using a single companion. Th ey are also designed to be obviously very alien (as they are part plant) so the player can accept any shortcomings as “natural” and more amusing than frustrating limitations in game technology |

The Thing The Thing | The player is in charge of a small squad of soldiers, and has to use them to move through the game. Your squad is driven by a “trust and fear” mechanic, where your team mates can secretly turn against you. | The trust and fear system put the agent behaviour and emotions at the centre of the game. Characters can have their trust in you increased by giving them weapons, or can be forced to carry out your orders by force - at a cost of trust by characters who witness this happening. Characters who have been with you for a long time become very valuable, and you find yourself protecting them as you play the game. |

Personal Trainers

| Game | Interaction | Attachment level |

|---|---|---|

EyeToy Kinetic EyeToy Kinetic | A fitness training 'game' which uses computer vision to help you exercise. Comes with a choice of trainers who help show you the moves you need to make and give encouragement and/or stern looks. | I found these characters were attempting to be too realistic and were rather annoying. I would have preferred a less obvious approach stylistically, and there was something about being chastised by them which really was quite amusing. |

Conclusions

Strategies used in increasing attachment to companions in games:

- Having companions dependant on you in some form (e.g. need feeding or rescuing) is a good way to build up a relationship.

- Graphical limitations don't affect attachment levels. In fact they probably help, in accordance with the uncanny valley.

- The use of natural language is one of the quickest ways to annoy the user, and break any illusion of intelligence, so it's generally left out, or a language which you can't quite understand is used instead, which still conveys basic levels of emotion.

- User investment in the design or construction of the agent increases a feeling of ownership, and therefore attachment - “My robot is the only one like it”.

- Collective intelligence is generally more robust, and likely to resolve in useful emergent behaviour than relying on a single agent.

- Migration of companions has been tried in games, and was generally seen as a successful experiment, the user accepting a large change in technology used to visualise the agent.