The Schwartz/Global Business Network Approach

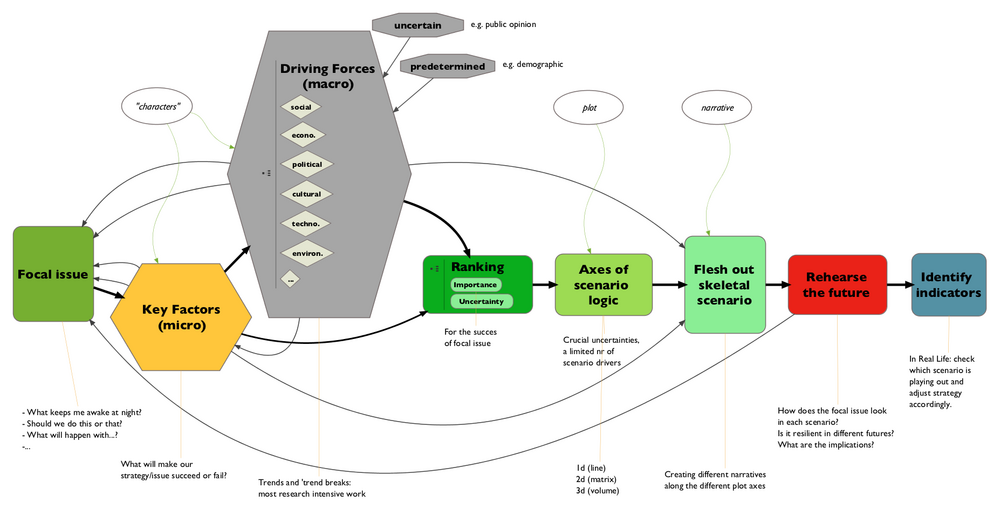

This approach outlines how to build a scenario based on the model presented by Peter Schwartz in The Art of the Long View. It is one of the most commonly used scenario methods. The process is quite simple and can be easily implemented by novice facilitators. This method creates evocative, albeit not too surprising scenarios, which tend to be useful caricatures of the present than radically imaginative futures.

The challenge of the method lies in its focus on scenario axes derived from critical uncertainties:

- reducing the number of change drivers to two critical uncertainties can create tension in participants (but can also work quite well in some situations, when it distills the core of the problem)

- the 2×2 matrix highlights 'opposites' and extreme scenarios, potentially losing the subtleties and diversity of the worlds.

At FoAM we use the Global Business Network (GBN) approach when a group has a complex but burning question. In these situations finding out what is most important and also most uncertain can illuminate the issue even without creating scenarios. Furthermore, it is simple enough that it can be completed in a one-day or even half-day workshop (with some online follow-up afterwards).

Process

Step 1: Focal Issue

Identify a focal issue / key question

Think about what is vital to your situation and formulate your focal issue as a question. A good way to start might be to ask yourself, 'What keeps me awake at night?'

The key question can be phrased as something specific, along the lines of 'Should we do A or B?' But you can also use more open questions, such as those starting with 'How do we…', 'What if…', 'What could happen…', etc.

It is essential to identify and explore the question with everyone involved and to agree that the question is fundamental for the future. Take your time to define a clear and memorable question and try to phrase it succinctly, as you will need to keep it in mind throughout the following steps.

Step 2: Factors

Map the local situation and identify important factors

Discuss what factors have an impact on the context or situation that will influence the outcome of your key question: people, places, resources (material, immaterial), history, technology, and so forth. Try to be specific and exhaustive. Make a mind-map of all the factors that together provide a complete picture of what influences the situation in the present.

If you prefer a more structured conversation, you can define the key factors using appreciative inquiry interviews, the KPUU framework, or other techniques described in the observing and mapping section.

Step 3: Drivers

Identify driving forces

Research what emerging forces have an impact on your local situation. Depending on whether you want to construct your scenario based on facts or more subjective assumptions of the people involved, you can do two things:

- Research in depth and breadth: make an extensive survey about what changes in the wider context in which you operate. In futurist jargon this is called 'horizon scanning'. One of the ways to direct your research is to look for societal, technological, economic, environmental and political trends (STEEPs or STEPs). Depending on how much time you have, you can spend an hour, a day, a week, months or years researching change drivers. Alternatively, you can commission or find open-access trend reports by foresight experts, potentially shortening your time spent researching.

- Collect drivers from the group: discuss and list the key driving forces as the people in the group perceive them. It can still be useful to go through the STEEP/STEP categories to help make a comprehensive list of drivers. The outcome of this exercise will be strongly coloured by the perceptions, assumptions and opinions of the people involved and might not provide an unbiased picture. This isn't necessarily a bad thing, just something to keep in mind.

Make a list of all the driving forces you have discovered.

Step 4: Ranking

Rank driving forces by their importance and uncertainty

Identify the most important driving forces for the outcome of your key question. You can rank them on a scale from 1–10 from least to most important. Alternatively you can use a more relative measure (e.g. drawing a horizontal line and placing the drivers from left to right: important → very important → extremely important → essential.

Next, identify which of the most important drivers are the most uncertain for the success of the core question from Step 1. Some drivers are likely to remain more or less fixed, constant and 'certain', like demographics, while others are mostly in flux and quite unpredictable, such as public opinion. You can rank the uncertainty of the drivers on a scale from 1–10, from least to most uncertain. Alternatively, you can use a more relative measure. One of the ways is to draw a diamond, with importance as one axes and uncertainty as the second one. By the end of this exercise, the most important and uncertain drivers will be in the top tip of the diamond, so they can be visually chosen.

List the drivers on a scale from most to least important and uncertain.

Note: When the local factors seem to be where the core issue of a group lies, we rank both the local factors and external driving forces based on importance and uncertainty. This means that our scenario axes could be a mix of internal and external forces.

Step 5: Critical uncertainties

Select critical uncertainties and design scenario axes

Select one to three (usually two) of the 'most important and most uncertain' drivers. These are your critical uncertainties which will constitute the axes of your scenarios.

Think about each of these critical uncertainties as a continuum from one extreme to another. For example, if you chose 'happiness' as one important and uncertain factor, your continuum might be from 'an ocean of tears' at one end to 'all smiles' at the other.

NOTE: You can choose more than two critical uncertainties, but that tends to make the process more complicated (you’ll have to develop multiple scenario matrixes, or work in more than two dimensions, which participants tend to find difficult to hold in their heads).

Plot the axes on a large piece of paper. If you have just one critical uncertainty, you’ll create two scenarios along a spectrum of one line, with two you’ll create a matrix and with three a volume. For more than three we would suggest creating multiple matrixes of two axes each.

Step 6: Scenarios

Create scenario narratives

Review what would happen with each of your critical uncertainties in different scenarios. Bring different change drivers and local factors into the scenarios. What would happen to them in different worlds? How did the wider world evolve from the present to this particular future? How did your local situation change? Who are the main protagonists in this world?

In a group, come up with an outline, a 'skeleton' of each narrative. This can be short and succinct, but should capture the 'essence' of the scenario. From these outlines you can then write out the scenarios as short stories. You can do this in smaller groups, or individuals can volunteer to flesh out the stories after the workshop and send them to others for edits and suggestions.

Step 7: Answers

Take a step back to get a sense what each of the worlds look like. How would you answer your core question (step 1) from each of the scenarios? What would your decisions look like in different futures? Explore what would have to happen to get from where you are now to the situation in the scenario. What opportunities and threats do you see in each of the worlds?

After a discussion, formulate a succinct answer to your core question from each of the scenario worlds.

Step 8: Signals and Indicators

Identify weak signals and other indicators in the present

Discuss the scenarios related to the actual situation and the people involved. Each of the scenarios in this exercise is more or less likely to unfold. It is interesting to observe which one the participants find most probable, which ones they prefer and which they dislike and why. Discuss the gaps and inconsistencies in the scenarios and find out where more information should be gathered from the micro or macro environments.

After getting a sense of how the group feels about the scenarios, identify trends or weak signals that could point to changes in the present moving towards one or the other scenario. Invite participants to use these signals to inform their decisions.

Adapted from: Peter Schwartz, 1998, The Art of the Long View: Planning for the Future in an Uncertain World, Wiley http://www.infinitefutures.com/tools/sbschwartz.shtml